The General and the Gift of a Good Start

What Colin Powell Can Teach Us About Children’s Health

In 2021, a remarkable man, whom I had the good fortune to meet several years ago, passed away due to complications from COVID-19.

General Colin L. Powell, USA (Ret.), was a passionate advocate for children. He was the founding chairman of The America’s Promise Alliance and served on the National Board of Governors of the Boys and Girls Clubs. A visit he made to the Boys and Girls Club of Delray Beach, Florida, in 1993 seemed to leave a lasting impact on him. Recounting it in his 2012 memoir, It Worked for Me: In Life and Leadership, General Powell offers this conclusion:

“You can leave behind you a good reputation. But the only thing of momentous value we leave behind is the next generation, our kids — all our kids. We all need to work together to give them the gift of a good start in life.”

-General Colin L. Powell, USA (Ret.)

Child Health Benefits All of Us

Abundant research tells us that giving a child a good start doesn’t just benefit the child. It benefits all of us as the ripple effects of physical and mental health, education, and productivity are felt across the economy. As I explained here , economists like James Heckman of the University of Chicago have found that investing in children yields exponentially high returns to society through reduced costs in education, health and justice system spending as well as through increased tax revenue. As Princeton economist Janet Currie explains, we have more than enough data to show us that child health is “an important form of human capital. Healthier children live longer and healthier lives, get more education, and earn higher wages.”

Many of our children in America are not getting the good start they need to live to their full potential. Fortunately, America has the know-how and the resources to fix this. We just need to harness a character trait that General Powell had in spades: the will to act.

Perseverance and Determination

Time and time again, Colin Powell persevered. With dogged determination, he not only completed one physically and mentally challenging training course after another, but he also excelled. Though he considered himself an unremarkable athlete and student, he became an airborne ranger, was quickly and repeatedly promoted, led men through the jungle in Vietnam, and earned an MBA from The George Washington University, all by the time he turned 35.

Based on his own accounts of his childhood, Powell grew up with a supportive family and access to high-quality education. He gives a great deal of credit to the City College of New York, where he attended college and joined the ROTC. When he attended, CCNY’s tuition was $10 a year – significantly more affordable than his other option, a private university (which at the time was $750 a year). Powell notes that the graduates of the college include a Supreme Court justice, two New York City mayors, nine winners of the Nobel Prize and Dr. Jonas Salk, who discovered the polio vaccine.

Facing “America’s Problem”

Many of the challenges Powell describes are related to tests of physical and mental endurance and intellectual rigor. But one challenge he faced arose from the very country he loved and defended. During his military training and as an officer at bases across the Jim Crow South, Powell describes encountering overt, pervasive racism to a degree that he hadn’t experienced growing up in New York City. “Racism,” he wrote, “was not just a black problem. It was America’s problem.”

Today, decades after the repeal of Jim Crow laws, systemic racism perpetuates health disparities in childhood and into adulthood. The American Academy of Pediatrics details the impact of racism on child health in this 2019 report, explaining that “Racism is a social determinant of health that has a profound impact on the health status of children, adolescents, emerging adults, and their families. Although progress has been made toward racial equality and equity, the evidence to support the continued negative impact of racism on health and well-being through implicit and explicit biases, institutional structures, and interpersonal relationships is clear.”

When General Powell spoke at a Nemours’ Children’s Health pediatric conference on child health in 2018, he talked to us about his work with children’s initiatives and how his experience drove his passion for investing in education. He shared his concern about the alarming number of 18-year-olds who want to join the armed forces but cannot due to criminal records, drug use, obesity, or inadequate school performance. His words only strengthened my resolve, already well-formed after decades of work as a pediatric surgeon and researcher, that children’s hospitals have a critical role to play in improving health equity.

Children’s Hospitals Must Lead

Many children’s hospitals were founded in the 19th and 20th centuries to deliver care to all children, regardless of race, gender, or ability to pay. In the 21st century, children’s hospitals are already at the forefront of this work, but we can and must do more to ensure that every child is given the gift of a good start. Children’s hospitals must take the lead by addressing the social determinants of health in communities across the nation through programs that improve access to medical care and education and remove barriers like systemic racism.

As General Powell said in his most recent memoir, “I am frequently asked why youth programs and education have become a priority in my life. My answer is very simple: I want every kid to get the chance I had.”

About Dr. Moss

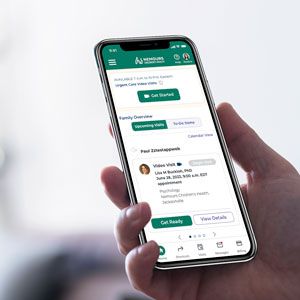

R. Lawrence Moss, MD, FACS, FAAP is president and CEO of Nemours Children’s Health. Dr. Moss will write monthly in this space about how children’s hospitals can address the social determinants of health and create the healthiest generations of children.